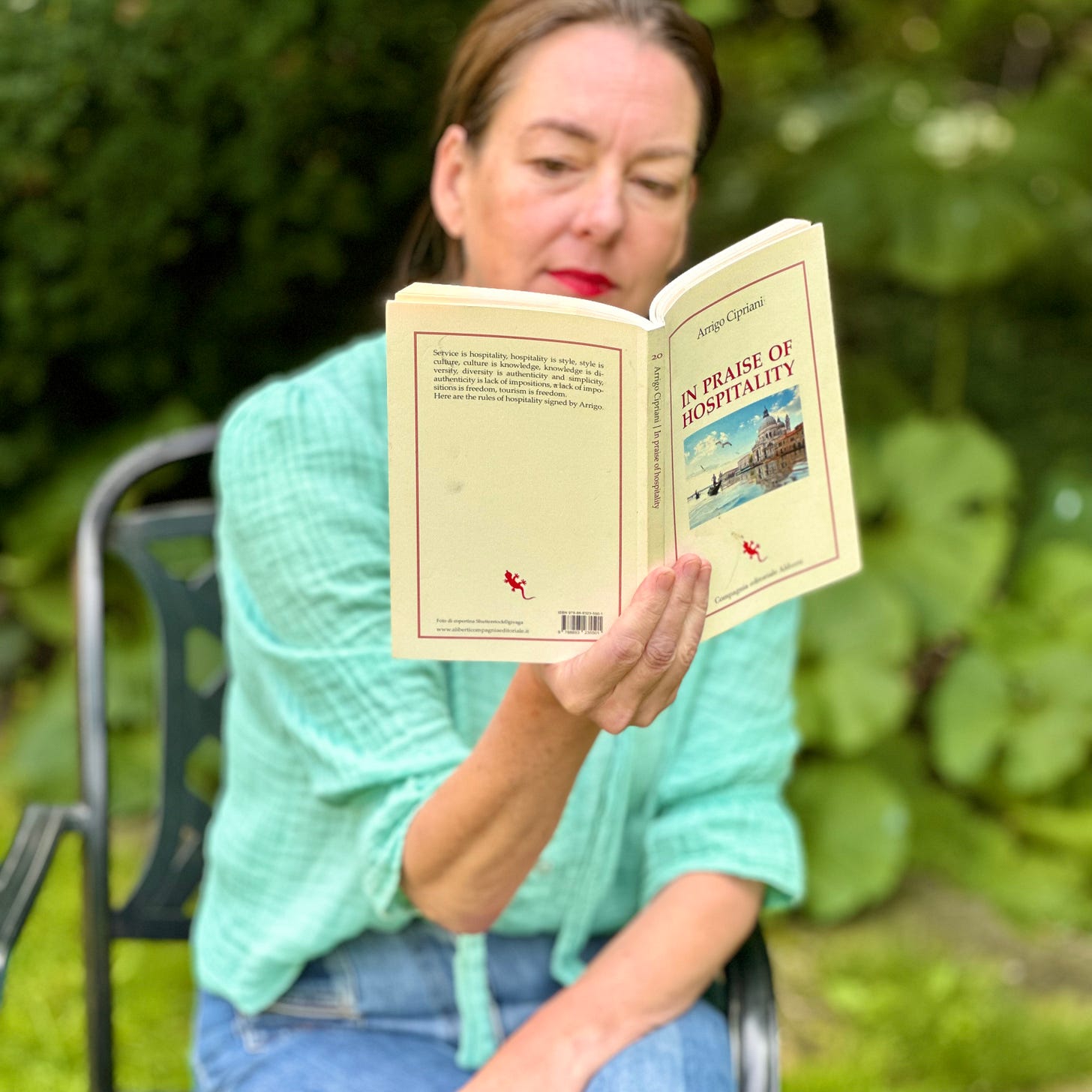

In Praise of Hospitality by Arrigo Cipriani is a slim volume that came into my hands this summer. I was so captivated by it that I read it twice in a row, and I have since been dipping back in because it has so many wise things to say.

Arrigo Cipriani is the man for whom Harry’s Bar in Venice was named. His father, Giuseppe, opened it just a year before “Harry” was born, in 1931, so he basically grew up in it. At the age of 92, he apparently still goes in every day. The family went on to create the Cipriani hotel, so Arrigo spent his entire life surrounded by some of the best examples of fine hospitality on Earth. And, of course, he grew up in one of the world’s most exquisite cities, Venice, which had a huge impact on his view of life, culture, beauty, and hospitality.

The Italian word “ospite,” which comes from the Latin, means both host and guest, which is lovely because it reflects how, ultimately, they’re one and the same. The root meaning of the word is “other” or “stranger.” “Hospite” (it takes an h in Latin) sprouted loads of related words, of course: hostel, hospital, hospice, hostile, hospitality…

Hospitality began as something for travellers, and it’s important to remember, looking back over time (and even today), that people on journeys were often on the move for unhappy reasons, such as fleeing persecution or looking for work or food. In other words, they weren’t sightseeing tourists but more likely persons in an hour of need, seeking the kindness of strangers to help them on their way.

Hospitality started in homes. Obviously, you’d have entertained friends and family, but you might also occasionally have had a stranger knock on your door whom you’d feed and, perhaps, allow to sleep in your barn for the night before they carried on their journey. The practice later became commercialized, with inns and restaurants. And, of course, it has a civic role, too: hospitality between governing bodies or ruling families or tribes has always been vital for keeping the peace. Today, hospitality has become a massive industry. Never have people moved around so much, at least not for the purposes of a good time.

But, no matter the type of hospitality, it is essentially an interaction between one human being and other. This fine point of emphasis – the human element – is one reason Cipriani wrote his book. He did it in the intimate form of letters, not unlike Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, only in his case to a young hotelier or restaurateur. A chief concern of his is that hospitality today is being dehumanized. He writes that tourists have largely been turned into anonymous consumers or mere statistics, and that service people have, for the most part, become robotic, lacking a human touch.

Here’s one passage from early on in the book that struck a chord with me: